In my role leading AI initiatives at MOCEAN, I’ve taken a curious and experimental position and still recommend other creatives do the same (in the spirit of keeping your enemies closer). But deep down, I’ve always had an uneasy feeling, knowing AI can only do what it does because it was trained on the sum total of human creativity.

You don’t have to look far in the comments of some AI videos online to find posts filled with resentment, decrying the displacement of human creatives, and often with a cancel-culture level of anger. While I don’t share that level of anger, I can relate to the source of it: that something about generative AI feels wrong.

But what exactly is wrong is hard to pin down: it’s not as simple as AI plagiarizing work, as it’s largely true that generative AI outputs are unique, with virtually infinite variations. And while AI can only do what it does because of its training data, the training data is only analyzed for its general qualities and not retained, so it’s not as simple as AI remixing copyrighted files or storing unlicensed material.

And yet, that sinking feeling persists. So I’d like to put forth a possible answer.

While generative AI isn’t trained to plagiarize creative works directly, it’s plagiarizing something far more personal: how our minds work.

Below, I dive into how I arrived at this conclusion by exploring three common defenses of AI, and what each reveals about how AI works, where it’s headed, and the ultimate ambitions of the major AI players.

Defense 01: Scraping the Internet is Fair Use

Under the Fair Use precedent (from 2010 when courts decided Google could digitize books to provide a searchable database of them), AI companies openly admit they analyze copyrighted works to train their neural networks. But this is where the legal sleight of hand comes in. What’s learned from that analysis is not the copyrighted work, but it’s “latent features”: the patterns, styles, structure, or approach to the work.

This means it’s learning things like sentence structure, visual layout, camera movement, color palette, illustrative and photorealistic styles, chord progressions, song structures, and even concepts like tone, voice, aesthetic balance, and physics.

This is explicitly stated in a publicly-available document by the lawyers for Suno, a leading AI text-to-music tool that’s being sued by the major record companies:

“It is no secret that the tens of millions of recordings that Suno’s model was trained on… included recordings whose rights are owned by the Plaintiffs [major record labels]… copies made solely to analyze the sonic and stylistic patterns of the universe of pre-existing musical expression.”

-Suno’s statement from court documents

The use of “solely” tries to downplay the unimaginable scope of analyzing “the universe of pre-existing musical expression,” essentially saying, “Hey, we’re just extracting the soul of every recorded piece of music since the beginning of history to learn how to make new music.” And yet none of this runs afoul of current laws.

So current models are allowed to analyze copyrighted material for free, learning from the best of human creativity, then are placed behind the paywalls of for-profit tools that enter the same marketplace of creativity from which its training data came. That sounds anything but fair.

Defense 02: AI outputs are unique, so not plagiarism

Generative AI models blend a host of influences from their training data to create outputs that are, by design, not exact reproductions of any singular source. This process means that while an AI may have been exposed to extensive libraries of text, images, or videos during its training, it does not store and retrieve these works verbatim. Instead, it combines patterns, structures, and stylistic elements in ways that are inherently variable.

Even if certain distinctive features from the training data appear in the output, they are within a broader, novel context that lacks the coherence of a sourced work. This distinction is crucial because the law typically protects the specific expression of ideas rather than the ideas themselves, and in the case of AI, the output is an amalgamation of influences rather than a clear, identifiable copy.

And given the unimaginably large datatset needed for these tools to work, any single item or latent feature gleaned from it is a minuscule percent of the whole. Put another way, perhaps AI is not yet seen as a kind of plagiarism due to the sheer complexity and scale of this particular kind of theft, to which our society's legal and creative institutions have not yet caught up. It’s like large-scale data laundering, hidden within the black box of neural networks, in which the copyrightable identity and latent artistic features of the works is transmuted into data that is deemed currently legal.

Defense 03: AI Learns Like A Person

One of the popular arguments for scraping the internet and training on copyrighted material is that it’s fundamentally the same as how humans learn. Just as people study books, watch films, or examine art to absorb ideas and become inspired to create their own work, AI “learns” from those same sources to generate new content. If we make it illegal for an AI system to learn from art, writing and music, the argument goes, will we next outlaw the film school auteur’s Kubrick references in his work?

But there’s a vast difference between what a single person can do and what a billion dollar AI-as-person can do. In the case of generative AI, its learning and creative output is on an industrial scale and speed never before seen in history, and well beyond the ability of any one or even a group of human creatives.

But this massive scale is key to every AI company’s ambitions, because of what they’ve discovered: When you train a neural network on billions of words, images, videos, or songs, these models start to learn something far beyond how any single creative asset is made. In a fireside chat, Ilya Sutskever, one of the founders of ChatGPT, spoke to CEO of NVIDIA Jensen Huang about this very subject:

“When we train a neural network to predict the next word from a large body of text, it learns some representation of the process that produced the text.”

-Ilya Sutskever, ChatGPT Co-Founder

And what is “the process that produced the text”? A euphemistic reference to the human mind. Using the legal precedent of fair use, AI companies like OpenAI are reverse engineering how our minds work by analyzing everything we’ve created.

For further evidence, here’s the expanded interview clip, where Sutskever explains what large language models actually learn by analyzing the statistical correlations in text (spoiler – it doesn’t just learn how to write):

Excerpt from fireside chat with Ilya Sutskever & Jensen Huang

Click here to watch full interview

The ultimate goal, as Sutskever says in the video, is to build World Models: with enough data, analysis and scale, AI models aim to effectively simulate the physics as well as the written and visual languages of the world, including the objects, animals, and people that live within them. The developers of Sora, the text-to-video model from the company behind ChatGPT, state this explicitly in their public research:

“Our results suggest that scaling video generation models is a promising path towards building general purpose simulators of the physical world.”

-Sora Developers

Think Midjourney is only trying to be the leading text-to-image generator on the market? This quote from their CEO states their bigger ambitions of a World Model:

“We’re really trying to get to world simulation. People will make video games in it, shoot movies in it, but the goal is to build an open world sandbox.”

-David Holz, Midjourney Founder & CEO

To put a fine point on it, Elon Musk posted the following cartoon to his account on X after an upgrade to his AI offering called Grok:

And this much-maligned Apple ad, even though it wasn’t specifically about AI, turns out to be a perfect metaphor for the World Model ambitions of AI companies, crushing all the objects of human creativity into a wafer-thin iPad:

So what do we do?

For those that remember the early days of digital music, you could compare this moment in AI to when Napster indiscriminately digitized and distributed songs, throwing the art and business of music into chaos. There’s no doubt Napster was an inflection point that – whether people fought or embraced it – radically transformed the music industry. But it also forced a legal and ethical reckoning around compensation for human creativity, one that I think we all feel is critical for AI to move forward in an equitable way.

There are close to 40 lawsuits working their way through the courts that challenge the legality of training on copyrighted material, with some aiming to show how what AI is doing is well outside the intention of the Fair Use precedent. Unfortunately, it could take years for these cases to get resolved, allowing current practices to continue to fuel AI’s explosive growth.

I’ve wondered if public sentiment will also play a role, as people wake up to how AI works and what impact it will have on creative industries. Will it be like what happened in the fashion industry when public awareness about the cruelty of animal fur in clothing sparked a backlash that changed industry practices?

While there’s a lot of unknowns, one thing is clear: however sobering the facts of AI may feel, it’s critical for the creative community to engage with AI, understand it, and work together to have an informed voice in the conversation. AI is not going away, and if we confront the benefits and threats of it with open eyes, we won’t either.

Further reading…

I highly recommend the brAIn, a newsletter focused on the legal side of AI by Peter Csathy, a lawyer with over 30 years of experience in media and entertainment. He includes a tab that tracks the current litigation working its way through the courts.

You can read and subscribe here: the brAIn by Peter Csathy

*Midjourney prompts

The following prompts created the images in this post:

“The AI Elephant In The Room”: A low angle side view of a gigantic elephant with elements of artificial intelligence to it, standing in a plain four-wall white room with hundreds of tiny people standing at the base of the elephant looking up at it, in a pop-art graphic style using black, white and red

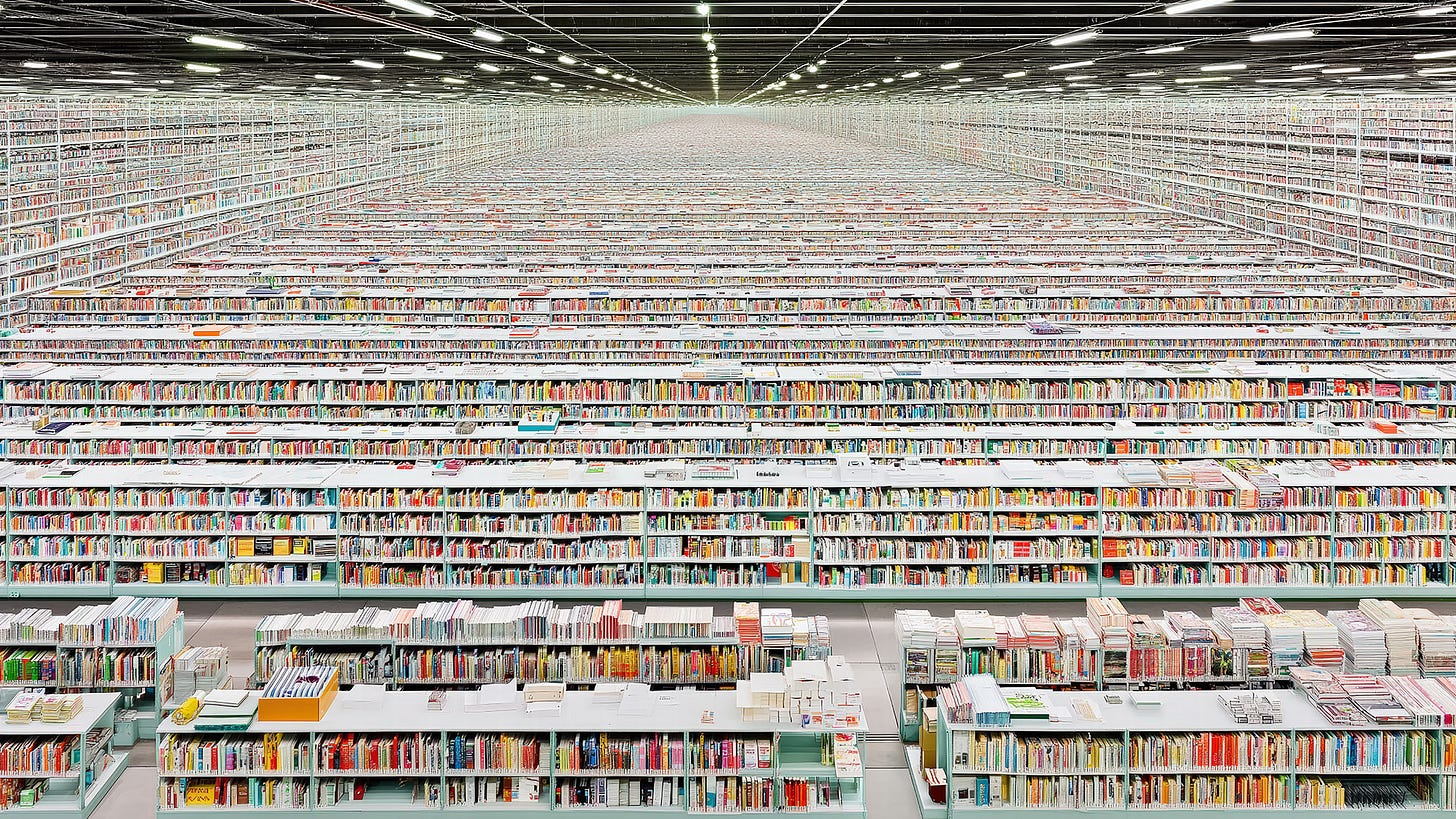

“AI Training Data”: An epic wide shot inside a massive warehouse, with thousands of rowed shelves with thousands of colorful books, artworks, and albums going off into infinity, high quality professional photography

Incisive well crafted and super relevant.

I agree with everything you said here, but economics aside, I actually believe the idea of being able to ingest, analyze and synthesize human knowledge is a good thing. Maybe the thing that bothers us is not so much that it is learning to imitate how our minds work, but the realization that we are not as amazing as we want to believe we are. The reason things like Suno work so well with music is that our artistic forms are actually much more rigid than we want to believe - otherwise we would not be able to distinguish and label virtually every style of music in just a matter of seconds.